Gastroesophageal reflux – sometimes called heartburn – occurs when stomach contents leak back, or reflux, into the esophagus. Heartburn that occurs more than twice a week may be considered gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Some people have GERD without heartburn. Instead, they experience pain in the chest, hoarseness in the morning, or trouble swallowing or bronchitis/pneumonia.

Symptoms/Diagnosis

When refluxed stomach acid touches the lining of the esophagus, it causes a burning sensation in the chest or throat. The fluid may even be tasted in the back of the mouth, and this is called acid indigestion.

What Causes This?

The esophagus is the tube that carries food from the mouth to the stomach. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is a ring of muscle at the bottom of the esophagus that acts like a valve between the esophagus and stomach.

If this sphincter does not function properly, or if it is not located in its usual anatomic position, stomach contents can reflux back into the esophagus. Occasional reflux is normal and usually does not cause any symptoms. When reflux occurs repeatedly, it can lead to erosion of the lining of the esophagus along with the symptoms of GERD.

Many factors contribute to GERD, but they can be divided into two main groups. The first group includes things that weaken the valve between the stomach and the esophagus. The second group causes reflux by increasing the pressure in the stomach so that it overcomes the LES.

Cause One: Weakening the LES

Hiatal hernia- This is a condition where the junction between the stomach and the esophagus (normally located in the abdomen) slides up and down between the chest and abdominal cavity. This can lead to weakening of the LES and reflux. Other outside agents that can weaken the LES include tobacco, alcohol, medications, and certain foods, like peppermint, or chocolate.

Cause Two: Increasing pressure in the abdominal cavity

Anything that adds pressure to your abdominal cavity can also cause GERD. Common causes include obesity, chronic coughing or straining, over-eating, changes in body position (bending over, lying down). Over time, chronic acid reflux can lead to changes in the cells that line the esophagus. This is known as Barrett’s esophagus. Patients can also develop pre-cancerous changes (dysplasia) because of chronic reflux. Once a patient develops these findings, careful and close follow-up is mandatory. This also includes frequent endoscopy to rule out development of cancer.

Treatment

Lifestyle Changes – If you think you are suffering from GERD, the first step is to see your primary care doctor. There are a number of lifestyle changes you can make that will help alleviate symptoms as well. These include:

Stop smoking

Do not drink alcohol

Lose weight

Eat small meals

Wear loose-fitting clothes

Avoid lying down for 3 hours after a meal

Raise the head of your bed 6 to 8 inches

Medications

Your doctor may suggest you try medication for your pain. A number of over-the-counter and prescription drugs, including antacids, foaming agents, H2 blockers, and proton pump inhibitors, can help you at this time.

If further workup is indicated, your doctor might recommend a barium swallow, upper endoscopy, pH monitoring examination, or an esophageal manometry.

Surgical Therapy

Who should have surgery? Most GERD will respond to lifestyle changes and medical management. People who do not respond to conservative management should consider surgery. Over time, the cost of the medicines can be significant and some patients will elect to have surgical correction. Studies have shown that results are better if the surgery is done before the patient’s GERD becomes severe (maximum medical therapy). Any patient who has developed Barrett’s esophagus or pre-cancerous changes (dysplasia) in the lower esophagus should strongly consider anti-reflux surgery. There are recent studies that report the regression of these findings in some patients who undergo the operation. Patients with Barrett’s esophagus or dysplastic changes who undergo the surgery should continue to have close follow-up, including endoscopy, on a regular schedule until the condition resolves.

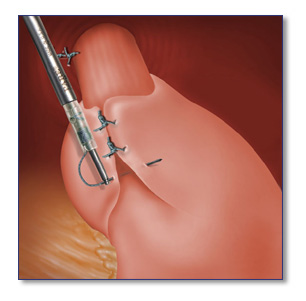

The standard surgical treatment for GERD is Nissen Fundoplication. In this operation, the upper part of the stomach is wrapped around the lower end of the esophagus, and the hiatal hernia is repaired.

This surgery can be done with the laparoscopic technique, which normally means less pain, a shorter hospital stay, a faster return to your day-to-day life, and an improved cosmetic result. Most patients at SCOSA will have this approach. Your surgeon will discuss this with you on an individual basis at your appointment.

Surgery: Before and After

Your SCOSA surgeon will review with you the risks and benefits of the procedure at your clinic appointment. You will be sent for some routine lab work, X-rays, and an EKG. In addition, your SCOSA surgeon will set up any further testing required to evaluate your esophagus before surgery.

On the day before surgery, you should have nothing to eat or drink after midnight with the exception of some medications. This will be clarified by your SCOSA surgeon. You should shower the day before or the morning of your operation.

Medications such as aspirin, coumadin, or other blood-thinning agents should be stopped at least seven days prior to surgery. Vitamin E, diet medications and St. John’s Wort should also be stopped at least one week prior to surgery. Please go over any specific questions with your SCOSA surgeon.

Patients are encouraged to stop smoking and begin an exercise program in advance of any operation.

The day of the operation

Your SCOSA doctor will give you detailed instructions about where and when you should be the morning of your surgery.

Once you arrive at the hospital, a nurse will start an IV, and you will meet with your anesthesiologist and your SCOSA surgeon to answer any last-minute questions. You will likely receive some pre-operative medications and then be taken to the operating room.

After surgery, you will be in the recovery room until you are completely awake.Your room will include a breathing device called an incentive spirometer. It is important that you use this several times each hour when you are awake. The nurses on the floor will give you specific instructions about its use. In addition, it is important that you get out of bed and walk in the hall. We like our patients to do this at least once the afternoon after surgery and then at least four times each following day. These activities are vitally important to prevent a blood clot from forming in your legs, pulmonary embolism, breathing problems, and pneumonia.

After-effects of Surgery

After the operation and for the next few weeks, patients consume what is referred to as a “post-nissen diet.” This is composed mainly of slippery food, like runny scrambled eggs or gelatin. In the four to six weeks after surgery, there can be swelling at the wrap, which narrows the opening to the stomach. Some patients will swell more than others and at times can have difficulty swallowing. Liquids and post-nissen diet provides nutrition that will pass smoothly through the opening. If solid food is taken too soon after surgery, it can irritate the lining of the wrap and aggravate the swelling – thus prolonging the transition to a regular diet.

Although this operation is very safe and has a less than 1 percent mortality rate, this is an important decision for you and your physician. Potential acute complications are rare, but can include bleeding, infection, damage to stomach, esophagus, spleen or other internal organs. Other less common risks are hernia, wound problems, need for open surgery or re-operation.

Some patients will experience abdominal bloating after surgery. Patients who have chronic acid reflux will tend to swallow air or saliva repeatedly throughout the day in an effort to push the acid back down into the stomach.

After this surgery, there is some swelling at the junction between the stomach and esophagus, which inhibits some patients from burping as they did before to expel the swallowed air. The air is then passed into the intestines and consequently patients may experience some bloating. The good news is that once the swelling subsides, most patients can burp normally. Also, after the surgery the air and saliva swallowing is no longer necessary although it is difficult for some patients to “un-learn.”

You should schedule a routine follow up with your SCOSA surgeon two weeks after the operation.

You should call your SCOSA surgeon immediately if you experience any of the following after this procedure: persistent fever of more than 101 degrees, persistent nausea or vomiting; worsening abdominal pain- uncontrolled by medication; increasing abdominal swelling; chest pain; shortness of breath; redness around or pus coming from incisions; or the inability to tolerate liquids.

Outcomes

Most patients spend one night in the hospital after this surgery, and then experience a complete resolution or a significant improvement of their symptoms.